Ángel Milagro, the Spanish engineer taking Japan to the Moon: “The idea is that by 2040 there will be a thousand people living there.”

Ángel Milagro planned the first privately funded lunar landing while sitting at his childhood school desk. The young aerospace engineer is the mission director for Ispace, a Japanese company valued at over €200 million. In Tokyo, he led a team of more than 20 specialists with one objective: to land a robotic probe on the Moon, something only the United States, China, and India had achieved at the time; no private firm had yet accomplished it. But it was 2022, and with half the world under lockdown due to the worst pandemic of the 21st century, Milagro was directing everything from his parents' house in Alfaro, a town in La Rioja with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, more than 14,000 kilometers from the Japanese capital. Every day, when he sat down to work, he would see old photos of his friends on the corkboard wall, pictures of the Spanish national football team celebrating the World Cup victory in South Africa, and one of his first childhood drawings: a spaceship.

“I’d always loved space, watching it on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, and all those channels from before YouTube,” Milagro explains with a smile in a café at Madrid Airport, just hours before returning to Tokyo. The 35-year-old specialist from La Rioja studied at the Polytechnic University of Madrid and worked for the European Space Agency on projects such as the Galileo satellite network in Germany. In 2022, stuck in a rut and confined by the pandemic, he decided to accept the offer to become a manager at the Japanese company, for which he is already designing his fourth mission, which will be his most complex yet.

“The idea is that by 2040 there will be about a thousand people living permanently on the Moon, and around 40,000 tourists a year,” the project manager ventures. In fact, he predicts that the young people currently studying engineering will be the first generation of professionals who can travel to the Moon to work.

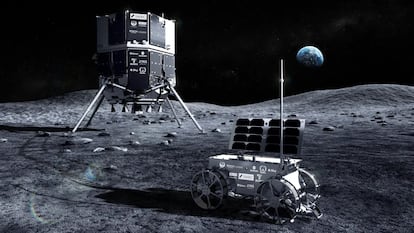

The driving force behind this new lunar conquest—this time focused on exploiting its resources—is the race between the United States and China to be the first to arrive . On the Western side, a handful of companies are launching support, transport, and initial exploration missions. The Japanese company Ispace is one of them, with a contract with NASA to land on the south pole in 2027. In this case, it will deploy a small exploration vehicle and several instruments to search for helium-3, an element that can fuel future nuclear fusion plants and is of great commercial interest on Earth, where it is scarce and crucial for medical imaging and quantum technologies. This summer, NASA announced that it expects to have a nuclear fission plant operational by 2030.

On April 25, 2023, Ispace's control center in Tokyo lost contact with its first spacecraft, Hakuto-R. The live broadcast showed the distraught faces of the entire team, including Ángel San , who had already managed to leave La Rioja and take command of his team in Japan. Hours, then days, of uncertainty followed until those in charge realized they had encountered one of the most common problems encountered when landing on the Moon. The module had passed over a crater, and the software was unable to handle it. Despite the probe's crash, company officials considered the attempt a success, recalls Milagro, as it had achieved most of its objectives, except for the last one.

This summer, mission control also lost contact with its second spacecraft, carrying Tenacious , a small exploration vehicle intended to be Europe's first to reach the lunar surface. It was a major setback, as expectations were much higher this time. The most likely cause of the failure was the laser that calculates the distance to the surface, which started working too late and couldn't prevent the probe from falling uncontrollably into the Mare del Frío (Cold Sea ), in the far north. “These sensors need to be validated in the specific conditions of the Moon, during a landing at 5,000 kilometers per hour. And it's very difficult to conduct relevant tests on Earth. For the company, it would have been better if the landing had gone well, but for the engineers, this failure has been a very important lesson, because it has taught us many things, albeit in the most difficult way,” argues Milagro.

Despite these two setbacks, the company is forging ahead with two other projects, one with NASA participation and the other in collaboration with the Japanese government. The first targets the same area of the far side of the Sun that the American astronauts of Artemis 3 will land on, scheduled for 2027—although there are serious doubts about whether this date can be maintained due to technical problems with its contractor, Elon Musk. The Japanese do expect to be ready on time. Their M4 mission will require a lander and two communications satellites to monitor the spacecraft from the far side.

Takeshi Hakamada, a 45-year-old Japanese aerospace engineer and science fiction and space enthusiast, is the founder and CEO of Ispace . His initial goal was to win Google's Lunar X Prize, and after the first financial setback, he founded this new company, which has raised hundreds of millions of euros in funding, although its shares have fallen sharply since this summer's setback. Other private probes, such as the Israeli Beresheet , and state-run probes, such as the Russian Luna-25 , which was headed for the south pole, also failed to reach the moon in 2019 and 2023, respectively.

Why is it so difficult to return, given that astronauts were sent there half a century ago? One explanation is money, Milagro acknowledges. “The budgets used during the Apollo program were virtually unlimited. The goal was to get there by any means necessary. Now, the aim is to make the trips profitable, to minimize costs and maximize benefits. That's why it's so complex,” the engineer explains.

Two US corporations have already landed on the moon, although only one was completely successful: Firefly Aerospace, in March . Ispace could still be the first from Asia and thus surpass Europe. The company's main objective is to conduct better ground tests that more closely resemble real-world conditions. The engineer from La Rioja is already focused on developing the fourth mission, while the third, part of NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, is being controlled from the US subsidiary. "It's very difficult," Milagro acknowledges, due to the enormous speeds—they might resort to tests aboard a fighter jet—but also because of the difficulty of recreating a surface with the same reflectivity as the regolith, essential for accurately calibrating the lasers. Despite the setbacks so far, the young engineer from La Rioja is confident that this time they will succeed with a "99% probability."

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(png)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fadc%2F1ba%2F352%2Fadc1ba352e9ea13bc27754ae38e2cad8.png&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(png)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F166%2F088%2Fd13%2F166088d13087ca066b45b8843dcaa609.png&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(png)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F4f0%2F592%2F54b%2F4f059254bae6aa60961f790e1798a8ac.png&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Ff88%2F035%2F714%2Ff8803571417ba3314006747fe60dcea3.jpg&w=3840&q=100)